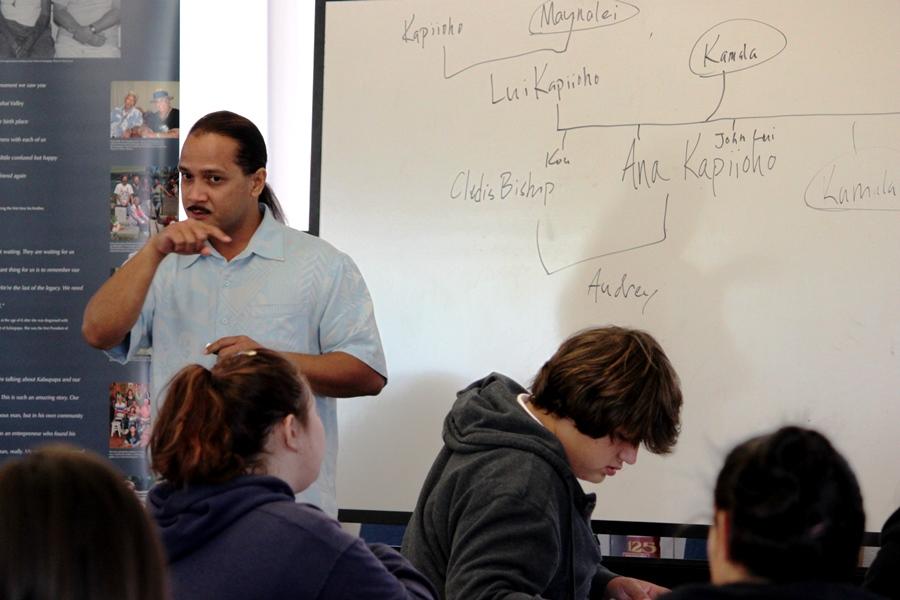

Ka ‘Ohana O Kalaupapa spoke to KSM students about Kalaupapa and the importance of remembering the stories of those who resided there on Tuesday, August 16.

Kumu Kapulani Antonio’s Hawaiian History students and other invited seniors and juniors could hear the presentation at three different times throughout the day in the Charles Reed Bishop Learning Center.

“I told them [the students] in the beginning that most stories are told by the conquerors, but this is the people’s history, and it comes alive through the people that tell it today,” Kumu Kapulani said.

Students learned about Ka ‘Ohana O Kalaupapa’s Names Project, for which the organization compiled more than 7,000 names of individuals who were sent to Kalaupapa, Moloka’i.

The preservation group archived the names for the use of the public in doing historical research. The group also plans to include the names in a memorial that is to be built there.

“I’m planning to go to Kalaupapa with Kahu [Kalani Wong] later on this month. I originally wanted to go just to help out with whatever I could, but their stories inspired me to go see if there’s anyone from my family who lived there,” said senior Corey Tanaka.

Several men and women shared stories about how they discovered they had relatives who were residents of Kalaupapa.

Councilmember Sol Kaho‘ohalahala was among those who spoke. During his first trip to Kalaupapa in 1996, he discovered he had ancestors who were sent there. “I was struck with a lot of emotion. Since that time, I’ve made the commitment to try to help and support the people of Kalaupapa in any way,” Mr. Kaho‘ohalahala said.

Ms. Maile Mossman shared how she learned more about her great-grandmother, Emma Waiamau, who was sent to Kalaupapa as a teenager. She performed a song she wrote for her great-grandmother and gave the students some homework, “Continue to learn your Hawaiian language and learn about your ancestors.”

Mr. Takayuki Harada had homework of his own to give to the students, “I want to encourage you to write.” Mr. Harada read several poems he wrote for his brother, Paul Harada, following his death in 2008.

Paul had been sent to Kalaupapa when Mr. Harada was one year old. The poems were included in Mr. Takayuki Harada’s book, Kalaupapa in Poetry, published last year.

“It inspired me to go to Kalaupapa to see if I have family there. We really should know our genealogy and find out who our ancestors are,” senior Tiasha Akre said.

Other speakers included the group’s treasurer, Ms. Pauline Puahala Hess and Mr. Kalapana Kollars, who is descended from Kalaupapa residents.

To close the presentation, Mr. Kaho‘ohalahala quizzed the students on their interest in Kalaupapa and spoke more about the upcoming Kalaupapa Memorial.

Ka ‘Ohana O Kalaupapa is a nonprofit organization whose mission is to promote the value and dignity of those who were diagnosed with leprosy and sent to Kalaupapa because of government policies at that time. Mr. Kaho‘ohalahala said that they meet with the administration of the Department of Health to try to resolve issues and concerns raised by the residents of Kalaupapa.

They visited Kamehameha Schools Maui as part of an outreach initiative toward the public and schools, which entails a series of presentations around the Hawaiian islands. They have at least two additional speaking engagements scheduled this month. One on Moloka’i and one in Honolulu.

Coordinator Valerie Monson said they hope to restore family ties by inspiring people to see if they have ancestry connecting back to the residents of Kalaupapa.

“It’s kind of like we’re taking the people of Kalaupapa back to their home islands,” Ms. Monson said.

Ka ‘Ohana O Kalaupapa was established based on the vision of Bernard Ka‘owakaokalano Punikai‘a, who was sent to Kalaupapa as a boy.

Kalaupapa is on a peninsula on the island of Moloka‘i. Residents of Hawai‘i who were diagnosed with leprosy, also known as Hansen’s Disease, were forced to move to the isolated settlement starting in 1866 under the Act to Prevent the Spread of Leprosy instituted by the state legislature under Kamehameha V. The mandatory isolation ended in 1969.

It is now a National Historical Park, with survivors still inhabiting the area.